The out world’s dreams are the currency

That grip the city streets

I live them out but I have my own

Hidden somewhere deep inside of me

In between my father’s fields

And the citadels of the rule

Lies a no-man’s land which I must cross

To find my stolen jewel – Johnny Clegg & Savuka, Third World Child

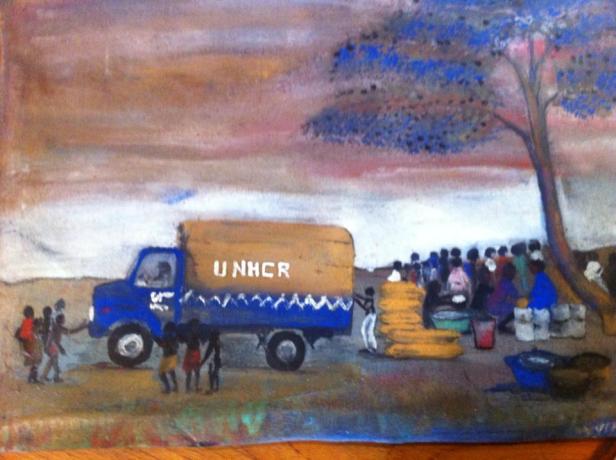

This song I heard live, drifting over Swiss cow fields into my bedroom. Johnny Clegg and Savuka were playing in the open air Paleo Music Festival, held between Geneva and Lausanne. It would have been the mid 90s. It was surreal to hear it. I had grown up listening to the album Third World Child. My parents had played the cassette tape often. For them, it held memories of my father’s first postings with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Botswana and Zimbabwe during the 1970s and 80s. My father would have negotiated inside no man’s lands in his line of work. He often repeated a story of an Angolan refugee with his child strapped to his back. He had been queuing at a UNHCR relief post.

“Why do you remember him?” I once asked

“He had this look in his eyes,”

“What kind of look?”

“It’s hard to explain. Also, it was the first time I’d seen a man carrying a child like that, it was usually women. And he just didn’t care.”

I like to think the look was one of the expatriated. And yes, I know that’s not a word. But at times we need to create news ones. My father still keeps this painting on the wall in his London house. Botswana was also the country where South African dissidents fled under apartheid South Africa. My older sister remembers my father telling her that when he had to work with white South Africans, they’d undermine him;

“Oh, you work for the United Nations High Commissioner for Terrorists?”

From Wikipedia, I learnt that Johnny Clegg was born in Lancashire, to an English father and a Rhodesian mother. Clegg’s mother’s family were Jewish immigrants from Poland, and Clegg had a secular Jewish upbringing. His parents divorced when he was still an infant, and he moved with his mother to Rhodesia and then, at age 6, to South Africa, also spending less than a year in Israel during childhood. He is know as Le Zoulou Blanc or The White Zulu in France and Switzerland. He is curiously very popular there. His mother bemoaned that the Zulus had stolen her son from her.

So there I was, approaching 15 years of age, listening to this song in a halfway house in Switzerland. My family was waiting for our house in France to be vacated by tenants. It was my 5th international relocation. I would have two more before I became an adult. I was in an infamously neutral country. Amongst my new classmates, I was the girl who had gone away long ago and had come back. And that was all my peers wanted to know about me. My international school, with a view of Lac Leman and France on the opposite shore, was a maze. I got lost trying to find the Art Room. Some students at school though it would be fun to play a joke on me. They sent me to the wrong place. I still recall standing at the top of this converted chateau in an empty room. The sun was streaming in through a window. It was a place of estrangement. It dawned on me what had just happened and I felt foolish and suddenly tired.

“What are you doing here? You’re not supposed to be here,” a teacher had scolded.

“I’m trying to find the Art Room,”

“Well, it isn’t here. The studio is on the bottom floor, on the way to the canteen.”

I heard snickering as I came in and was marked down as tardy. The lesson was pencil drawing. I drew what you see in the featured image. The Art teacher was very encouraging and on the big tree at the bottom right you can see her hand trying to teach me detail. She asked me what its title was.

“No Man’s Land,” I responded

“Oh?”

I had heard the term recently in History class whilst learning about World War 1. I had been fascinated by these strange areas of geography. Today I understand that it was because I had inhabited them. I had been a bystander. I had been in bubbles looking out but also looking into them. I too needed to cross or wait out a no man’s land to find a safe harbour. Many third culture kids have to actually fashion one out for themselves when they become adults. And that it is what I’ve done for myself. Born in 1979 in a Dutch Mission Hospital in Mochudi, Botswana and today in a suburb of Den Haag in The Netherlands. The midwife who delivered me was called Anneke and I was almost named after her. I will wait here by the North Sea until a last migration to England. I don’t live in No Man’s Land any more.

http://www.electives.net/hospital/5248/preview